Jesus Gonzalez

October 29, 2013

Whether American comics are better, more entertaining or artistic, than Japanese comics (Manga), or vice-versa, is completely subjective and irrelevant. However, there are far too many differences between the two to simply identify them as being one and the same. After all, people who enjoy American comics often dislike or ignore Japanese manga (the opposite is also true) indicating that though they may be composed in the same medium, there are some differences between how they approach their audience and articulate their message. The pacing of the story, the flow of information from panel to panel, as well as the degree to which one employs a cinematic approach differentiates one from the other, comics from manga.

The United States and Japan at a cultural level are significantly different and just as their cultures move at a different rhythm––at a different pace––so too do their comics. Scott McCloud in his comic Understanding Comics explains two different factors that affect the pacing of the story. The first is the over all length of the comic. In Japan as McCloud mentions “comics first appear in enormous anthology titles’ where each individual manga is not pressured to show “a lot ‘happening’”( 80). These anthology titles McCloud refers to are actually weekly published magazines that include one chapter (normally consisting of 16-19 pages) of each manga they currently run. For example, Weekly Shonen Jump, probably the most popular manga magazine outside of Japan, currently publishes approximately 21 different manga each week (sometimes more), making it about 350 – 500 pages long. After a manga reaches a certain number of chapters or is ended by the magazine, a 200 to 300 page tankobon, the Japanese word for “standalone book,” is created and published (Gravett 14). From this information we can safely assume that McCloud’s theory that the longer-length manga invites its author to devote several panels to “slow cinematic movement” is indeed correct (McCloud 80). Nevertheless, it is erroneous to assume that because manga are published in “enormous anthology titles,”unlike comics which are published independently in a monthly issue, they are less pressured to show “a lot ‘happening’” (80). In fact, the exact opposite is often true. Bakuman, a manga by writer Tsugumi Ohba and illustrator Takeshi Obata, the same team responsible for Death Note, portrays through the eyes of two young men seeking to become manga artists, or mangaka in Japanese, just how stressful and important it is to continue releasing meaningful work on a weekly basis to outshine their competition within the same weekly magazine. In essence, it is very much competition that prevents a manga from becoming dull and stagnant, because, if it does, the manga’s rating in the weekly polls would drop, and it would eventually be up for cancelation. In the United States, however, if the comic is a classic, especially superhero comics like The Amazing Spiderman, Batman, and X-men, it is safe from any sort of cancellation. The authors may be replaced, but the hero and story themselves will remain.

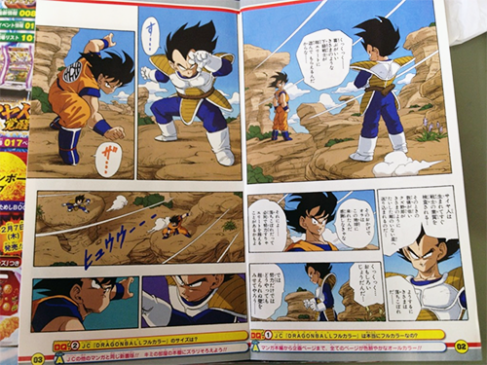

Manga’s length does indeed welcome “slow cinematic movement,” but it does not detract the manga from having a lot happening. Why is its pacing slower than that of the American comics? The answer lies within the second method McCloud discusses in Understanding Comics, the art of intervals, an Eastern specialty (81-82). The art of intervals, as defined by McCloud, “is the idea that elements omitted from a work of art are as much part of that work than those included” (82). The best example I can come up with from the top of my head comes from the manga Dragon Ball Z, where before an epic battle commenced, or during it, there was a page or two specially dedicated to silence (usually a stare-down between the two combatants) with only a gust of wind breaking it. The panels of silence before the fight help build the suspense and tension of the moment to the highest point possible before all hell breaks loose and the moment everyone has been waiting for finally begins. In other words, the panels with “slow cinematic movement” and even those that set up the mood do so much more to make the story exciting for the audience than going straight into the fighting scene would.

(Manga: Dragon Ball Z by Akira Toriyama. The bubbles in left page are only sound effects not dialogue.)

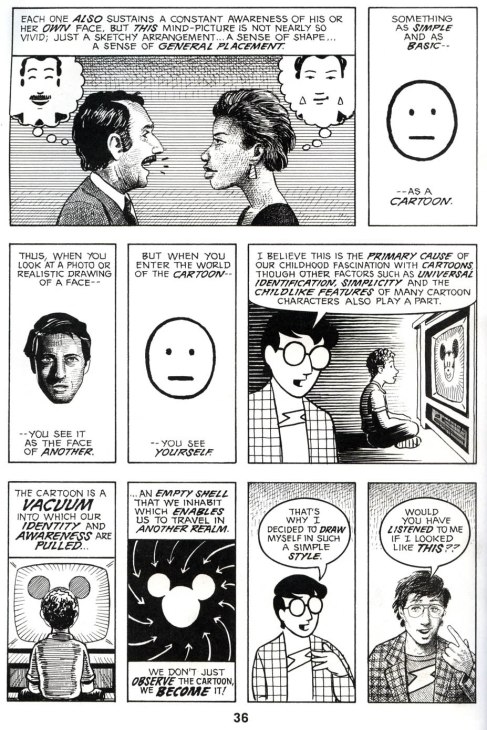

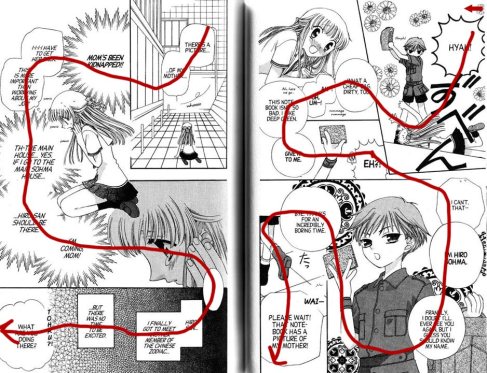

Another factor that differentiates Western and Eastern comics is the flow of information form panel to panel. For the main part, comics (including graphic novels) in the U.S. follow the rule to read from left to right and then up to down; if that fails follow the art and speech bubbles (Folse). On the other hand with manga, the reader should first attempt to follow the art and speech bubbles before following the right to left and up to down rule (Folse). This structural difference between the two may very well be the biggest, most fundamental difference between the two styles. Comics (some newer comics being the exemption) take a very direct approach to the medium by giving you information mainly at the top or end of every panel and then an image that goes along with the information. Because comics have less flowing panels, the gutter, the space between panels, in U.S. comics is so much more apparent than in manga. Unlike comics, manga attempts to guide the readers throughout the page telling them were their eyes should be going next, to the point were even reading backwards (from left to right as shown in the above image) seems rather natural. Owing to the fact that there is a seamless flow between the panels, the reading of manga is generally much faster than that of comics. Taking both the pacing of the story and flow of information form panel to panel into account, individual pages and chapters from comics will commonly take longer to read than those of manga, but will contain more information regarding the story and plot.

(McCloud’s Understanding Comics comic, follows the up to down rule.)

(Manga: Fruits Basket. Image Taken from Stephanie Folse’s article in www.hoodedutilitarian.com)

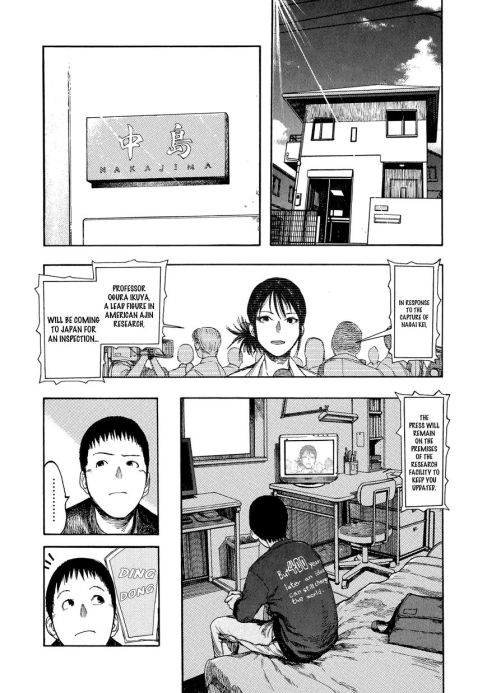

Lastly, the cinematic approach of comics and manga are at odds with each other. Comics, as McCloud points out, are very straightforward and thus contains a large majority of action-to-action panels, these panels show a single subject undertake or undergo a series of connected actions (McCloud, 70). Although manga may also have a high number of action-to-action panels, it incorporates other types of panels rarely seen in comics. The most prominent is the aspect-to-aspect panels, which normally do not deal with action and time but rather focus on presenting different elements of a specific place or mood (McCloud 72). Western audiences, believe it or not, are very much accustomed to the aspect-to-aspect panels. As far as I know, every single film uses this technique in order to establish the mood and setting of the current scene. Manga uses this panel style, in combination with their abundant use of subject-to-subject panels, that switch between subjects within the same scene or idea (McCloud 71). Usage of such panel relations tends to make manga more cinematic than their Western counterparts. Frequently in manga aspect-to-aspect and subject-to-subject panels are silent or have little dialogue in order to remove any crowding that would detract focus from the characters, as shown in the image from the manga Ajin. It is also important to note that during these silent panels any distracting background is removed. In Ajin the author puts as many details of the setting as he possibly can in panel 4 but removes all background noise by panel 5. In short, panel 4 establishes the setting for the following two panels, while they themselves focus on the character. By focusing on the character, readers are able to understand what is going on at emotional level. This style gives the characters a movie-like level of complexity. Some comics do use this same technique but the impact of these panels is somewhat inferior, because they are often lost within all the action-to-action panels and not highlighted well enough.

(Manga: Ajin by Miura Tsuina and Sakurai Gamon. Read from right to left. Panels 1- 2 are considered aspect to aspect because they present the setting. Panels 3 and 4 are considered subject to subject as they switch focus from the reporter to the teenager watching the news report.)

As discussed in this essay, fundamental differences between comics and manga can be found in the pacing of their story, the flow of their panels, and whether or not they take cinematic approach. Having a preference for one over the other is entirely subjective to ones own opinion.

Works Cited

Folse, Stephanie. “Visual Languages of Manga and Comics.” The Hooded Utilitarian RSS. N.p.,

28 June 2010. Web. 30 Oct. 2013.

Gravett, Paul. Manga: Sixty Years of Japanese Comics. New York: Collins Design, 2004. Print.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: William Morrow, 1994.

Print.